1910s-1920s: Japan in Transition from Meiji to Taisho era

- TNJ

- Sep 28, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2025

Emerging from the sweeping changes of the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), Japan entered the Taisho era (1912–1926) with a newfound sense of modernity. This period is often described as the dawn of modern Japan, when politics, culture, technology, and international influence reshaped the nation into a global power.

Political Transformation and the Taisho Democracy

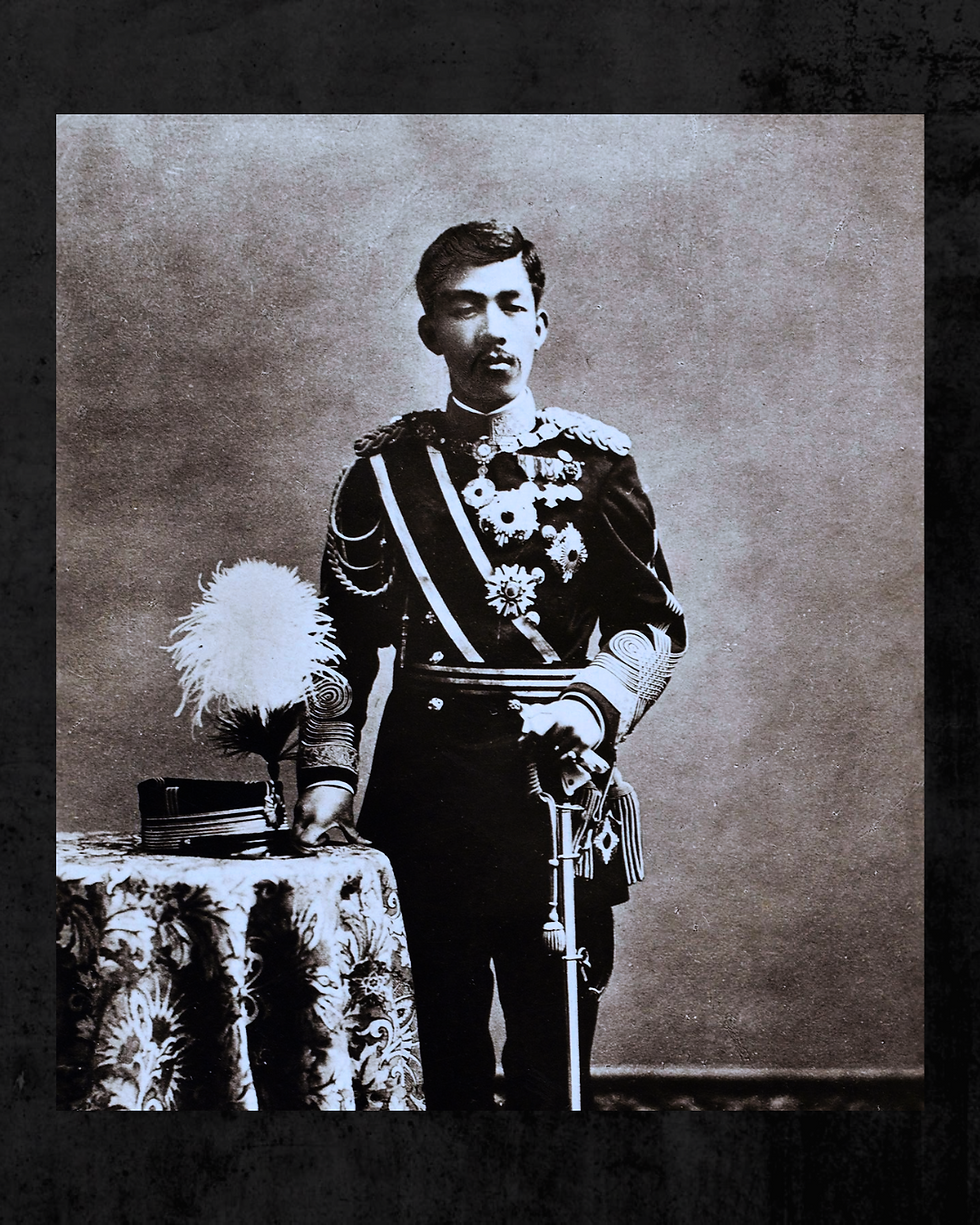

After the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912, Emperor Taisho ascended the throne.

His reign encouraged what historians call Taisho Democracy, characterized by growing political participation, stronger parliamentary influence, and the rise of new political parties.

While still a constitutional monarchy, Japan in the 1910s experienced more liberal movements, open debate, and civic engagement.

Japan in World War I (1914–1918)

Japan’s entry into World War I on the side of the Allies significantly boosted its international standing.

Seizing German territories in East Asia and the Pacific, Japan expanded its empire and solidified its position as a rising world power.

The war also accelerated industrial growth, laying the foundation for Japan’s modern economy.

Cultural Renaissance in the 1910s

The Taisho period culture is often remembered for its vibrant mix of Western influence and Japanese tradition. Cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka became cultural hubs, producing new artistic and social movements.

Literature and Art

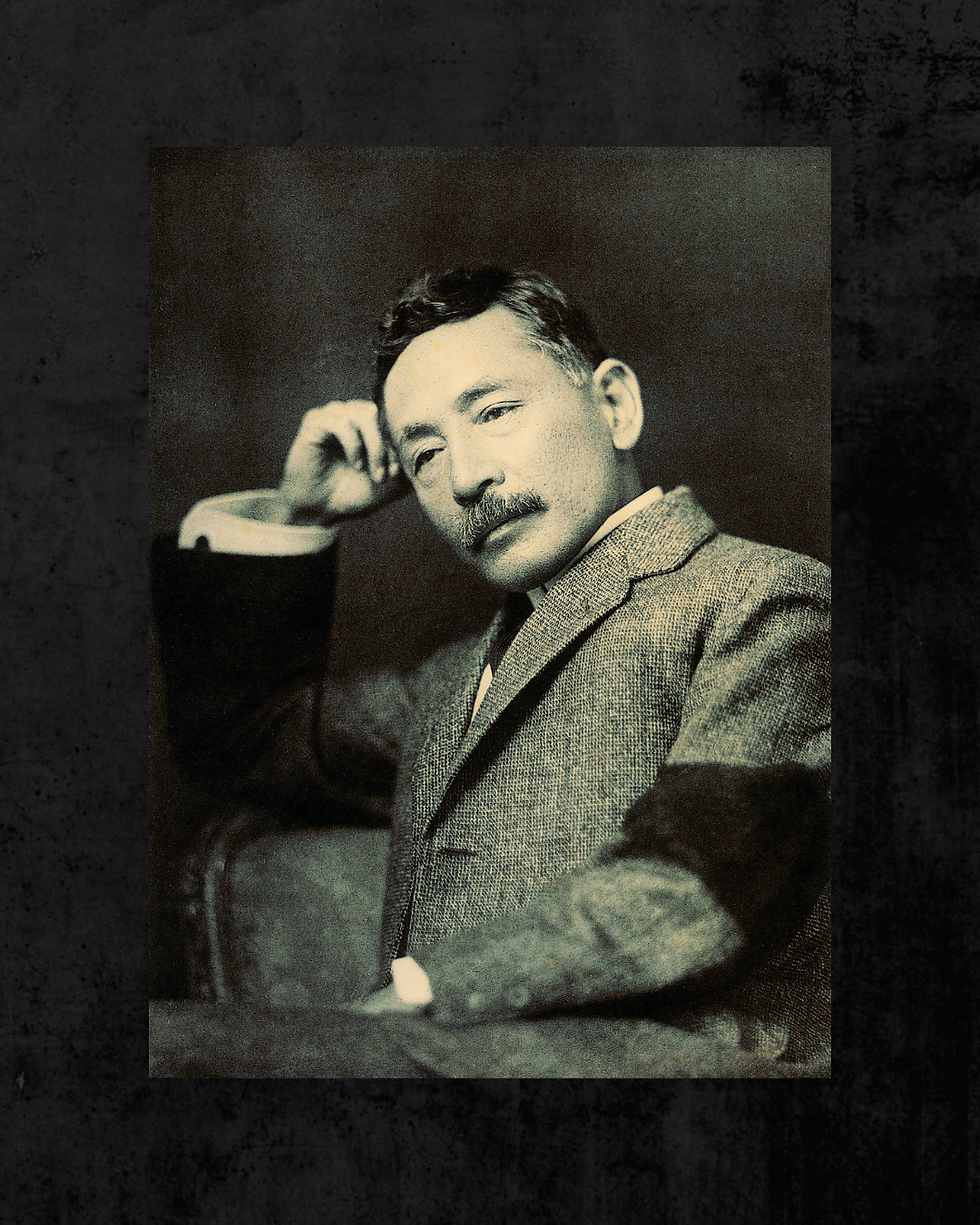

Writers such as Natsume Soseki and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke reflected modern anxieties and identity in their works.

In his 1910 novel The Gate (Mon), Natsume Soseki described the quiet life of an ordinary couple:

“Under the sun the couple presented smiles to the world. Under the moon, they were lost in thought: and so they had quietly passed the years.”

At first, it sounds like a simple scene of daily life. But behind these words is Soseki’s view of the Japan of his time — a country stepping into the modern age, filled with rising nationalism and social change. On the surface, people showed harmony and confidence to the world, just as the couple “smiled under the sun.” Yet in private, many carried unspoken doubts, quietly wondering about their own place in this rapidly changing nation.

Through such gentle lines, Soseki revealed something powerful: that even in an era of strong national pride, the inner life of individuals remained full of uncertainty and reflection.

Literary magazines and newspapers flourished, shaping intellectual debates.

Western-style painting (yo:ga) and Japanese-style painting (nihonga) coexisted, while woodblock prints remained a popular medium.

Architecture and Design

Modern Japanese architecture blended Western stone and brick construction with traditional wooden aesthetics.

Urban growth saw the rise of Western-style cafés, department stores, and theaters, changing everyday city life.

Music, Theater, and Film

Japanese popular music (ryūkōka) began developing, influenced by Western melodies.

Kabuki theater thrived, while modern theater (shingeki) introduced realism and contemporary themes.

Silent films gained popularity, with benshi narrators bridging traditional storytelling and modern cinema.

The Taisho Era in Kimetsu no Yaiba (Demon Slayer): Tradition, Change, and Inspiration

Today, many people know the Taisho era (1912–1926) not only from history books but also through popular culture. The world-famous anime Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba is set in this very period. Its mix of traditional Japanese landscapes with modern touches — Western clothes, steam trains, and electric lights — reflects the cultural crossroads of the time.

It’s no coincidence that creators might have found inspiration in this era. The Taisho years were marked by both optimism and anxiety: a wave of modernization, yet also fragile beauty and uncertainty. That tension between light and shadow, tradition and change, is exactly what gives Demon Slayer its unique atmosphere and emotional depth.

Fashion and Lifestyle

The 1910s saw a shift in Japanese fashion, with urban men adopting suits and women experimenting with Western dresses alongside the traditional kimono.

Cafés, jazz bars, and modern dining introduced Western food culture into Japanese daily life.

Western modernist designers and architects looked to Japanese aesthetics — simplicity, asymmetry, and natural harmony — as a counterbalance to overly ornate European styles.

The kimono, folding fans, and Japanese motifs (cherry blossoms, cranes, waves) remained fashionable in Paris, London, and New York.

Economic Growth and Modern Industry

Japan’s economy thrived during the 1910s, fueled by exports and wartime demands.

The textile industry, shipbuilding, and heavy industry grew rapidly, helping Japan become one of the leading industrial nations in Asia.

Modern banking systems and infrastructure development, including railways, electric trams, and urban housing, changed the face of Japanese society.

The period between 1910 and 1920 was not only a decade of political and economic expansion, but also the era that truly set the stage for modern Japanese culture.

From literature and fashion to architecture and music, the 1910s represented the fusion of East and West that shaped Japan’s modern identity.

By 1920, Japan had transformed into a nation that balanced tradition and innovation, setting the groundwork for its cultural and global role in the 20th century.

Comments